Foundations, Then and Now: Reading Michael Burry’s 1999 in a 2025 Bubble

What Coke, AmEx, Disney – and Sand Hill Road in 1999 – still teach us about AI blue chips and fin-Twitter today

This is a PickAlpha Biweekly Deep Dive Special Edition.

At a glance

Great businesses, bad decades. Using Burry’s Coke / AmEx / Disney examples, we show how world-class franchises can still deliver 50–70% real drawdowns if you combine peak multiples with the wrong inflation and rate regime. Our model shows the largest long-horizon losses come from “untouchables” bought at the wrong time, not from obvious junk.

1999 message boards = 2025 fin-Twitter. The names changed from AerotI on a titanium thread to obscure fintwit/Substack accounts, but the problem is the same: separating one informed voice from a sea of dopamine. Our view is that information density has exploded since 1999, while the number of people doing independent 2am modeling has arguably shrunk.

Value investing must mutate to survive. Burry’s path from Graham to Buffett to his own playbook is a template for 2025: the margin-of-safety principle still works, but the implementation has to adapt to passive flows, derivatives and AI-augmented narratives. This piece reads his 1999 through that lens – and asks what today’s AI blue chips might look like on a 1970s-style chart.

Reading Michael Burry’s “Foundations: My 1999 (and part of 2000)” felt less like nostalgia and more like a mirror held up to 2025. The tickers have changed, the plumbing is different, but the underlying behaviors – the way great businesses get abused by bad entry points, the way crowds chase stories, the way a few obsessive people do 2am work while everyone else refreshes quotes – haven’t moved much since Sand Hill Road in 1999.

What always jumps out in Burry’s recollections isn’t just the bubble. It’s how brutal time can be even to great franchises when you marry them to the wrong price and the wrong macro regime. His Coke / AmEx / Disney examples from the 1970s–1980s are the part most investors still don’t internalize: you can have a world-class business compounding intrinsic value, while the shareholder lives through a real 50–70% capital loss once you adjust for inflation and starting valuation. Our model shows the ugliest 10–15 year drawdowns don’t come from junk; they come from beloved franchises bought at peak optimism, high multiples and the wrong inflation/interest-rate backdrop. When you look at parts of the 2020s “AI blue chip” and mega-cap complex through that lens, the shapes start to rhyme in uncomfortable ways – different narratives, similar payoff geometry. For anyone who didn’t live through it, the optimism even showed up in hardware. Those translucent iMacs in Blueberry, Strawberry, Tangerine, Grape and Lime felt less like computers and more like fashion accessories for the dot-com decade.

iMac 1999 Press Photos

The way he describes message boards back then also feels eerily close to today’s fin-Twitter, Substack and Discord. In 1999 it was AerotI on a titanium thread. In 2025 it’s one obscure account, one throwaway chart, one 8-K footnote buried under a thousand dopamine-optimized posts. The information density today is probably hundreds of times higher than in 1999, but the number of people willing to independently build and maintain a model might actually be lower. Our view is that the real edge hasn’t shifted: it’s still about having a framework that lets you recognize “this person actually knows what they’re talking about” before the crowd does – and having the discipline to ignore ninety-nine loud narratives to act on the one quiet, correct one.

Burry’s own path from Graham to Buffett to “his own thing” is a good reminder that “value investing” isn’t a museum piece. Graham’s world was closed-end funds at 40% discounts and industrials on 5x earnings. Buffett’s world layered on durable brands, float and quasi-monopolies. Burry’s world added internet platforms, options, CDS and chat boards. Ours now has passive flows, factor crowding, structured products, AI-augmented research and real-time macro. The principle of margin of safety travels well across regimes; the implementation absolutely does not. What Burry was doing with ValueStocks.net – hand-built fundamental work, written out in public, timestamped – is, in a sense, what many of us are still trying to do in 2025: systematize that 2am research process so it can survive higher frequency, more derivatives, sharper cycles and louder noise.

The personal fork he describes – choosing to invest his father’s wrongful death settlement instead of paying down loans – is a sharp antidote to the “of course this was inevitable” mythology that grows around any famous investor. Seen from 2025 it feels obvious that the neurology resident on Sand Hill Road who wrote late-night value posts would end up running a fund and shorting a bubble. Seen from 1999, it was anything but obvious. It was one young doctor reading in a converted movie theater in Nashville, typing on a modem at midnight, allocating $10 a month to a message board, and then making a single choice about $50,000 that could just as easily have gone to Sallie Mae. There’s more path dependence and dumb luck in that story than most people are comfortable admitting.

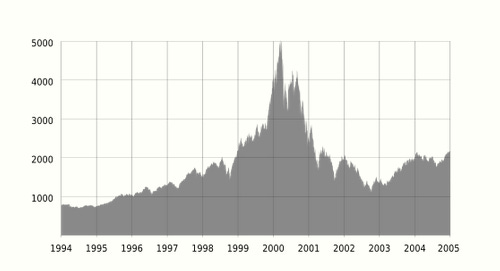

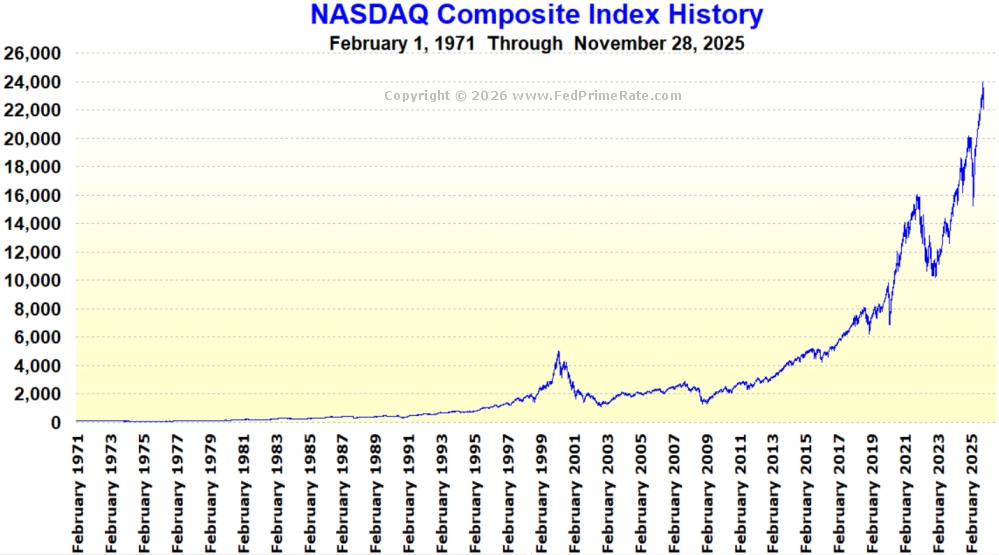

The NASDAQ Composite index spiked in the late 1990s and then fell sharply as a result of the dot-com bubble

That, to us, is also why the “plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose” line in his piece hits so hard. In 1999, the bubble lived on NASDAQ.com, CNBC, stock-checking terminals in hospital clinics. In 2025, it lives on X, Substack, AI-generated research, crypto, and whatever the next distribution channel is. Different interfaces, same underlying cycle: narrative → FOMO → leverage → policy response → long hangover. Our model shows that if you strip away labels and simply map flows, valuations and macro regimes, the late-1990s and early-2020s don’t look like distant relatives; they look like cousins separated by twenty-five years of technological progress and zero years of human progress.

And then there’s the compulsion. Burry is very honest about the fact that writing and investing at odd hours felt less like a career plan and more like something he “could not control.” That detail will ring uncomfortably true to anyone who has ever sat at a screen at 1am trying to reconcile a model, tweak an assumption or finish a draft while the rest of the world is sensibly asleep. The tools we use in 2025 are sleeker than dial-up and MSN Money, but the pattern is the same: the people who end up slightly ahead of the cycle are usually the ones quietly doing boring work in unglamorous time slots.

In that sense, Cassandra Unchained reads like a high-bandwidth continuation of what he was already doing with ValueStocks.net: carving out a corner of the internet where someone is willing to timestamp uncertainty in real time, rather than only posting polished hindsight after the crash. For those of us who didn’t live 1999 as investors, this series is as close as we get to feeling the texture of that bubble from the one guy on the ward who wasn’t refreshing quotes between patients – and to asking what we might be missing, right now, in our own version of 1999.

In the next Forward Valuation piece, we’ll stress-test one of today’s AI “untouchables” against the same 1970s playbook that punished Coke, AmEx and Disney.