SpaceX’s valuation is the most contested number in private markets because people keep trying to price it like a single company.

It isn’t.

It’s at least three businesses stapled together – launch, connectivity, and a portfolio of moonshot options – all amplified by a founder who explicitly wants to spend cash flows on outcomes Wall Street usually discounts as “non-core.” In the last week alone, SpaceX’s CFO described an insider share sale valuing the company around $800B, and said the firm is preparing for a possible IPO in 2026 – with the fine print that the timing and valuation are “highly uncertain.”

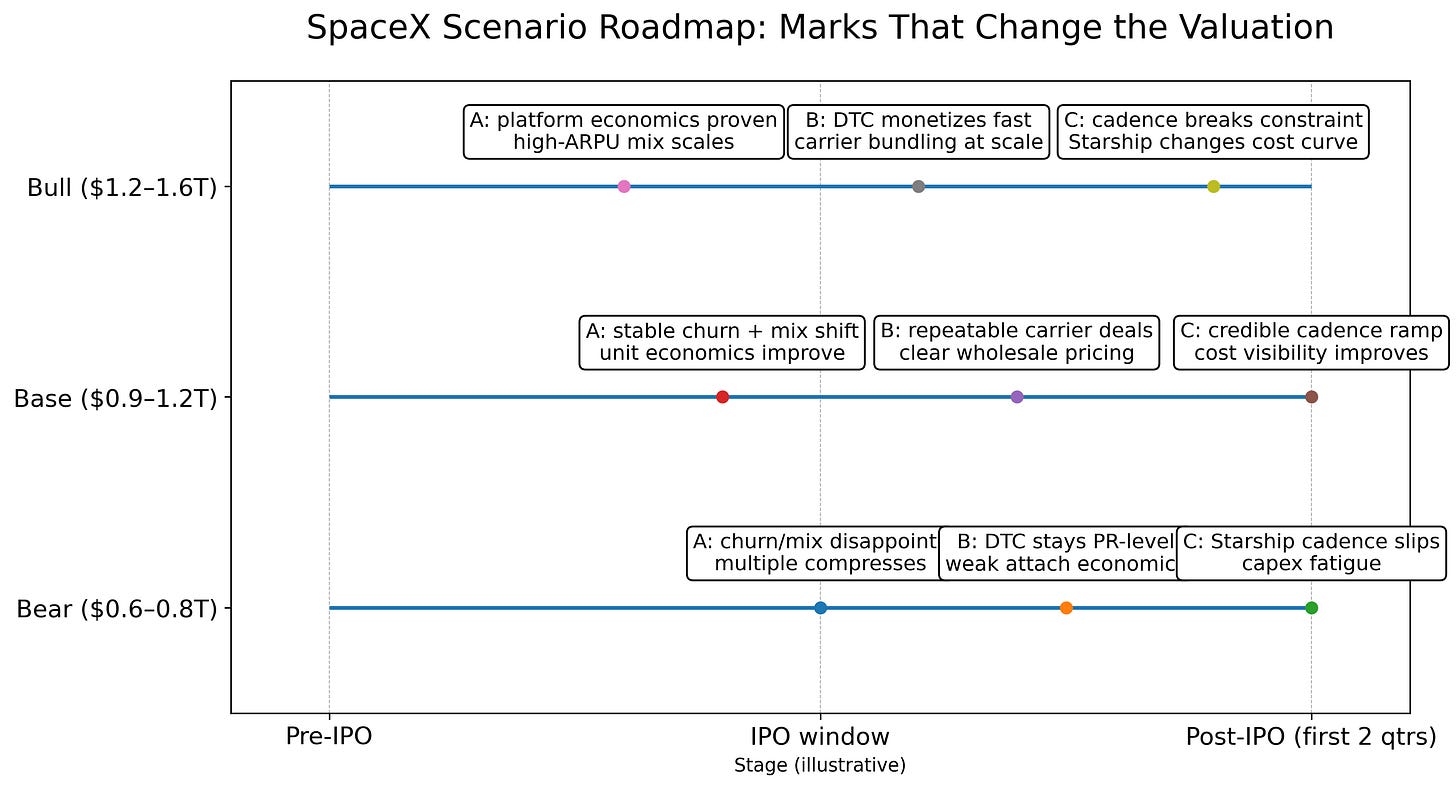

Chart - Three marks that move SpaceX from ‘industrial’ to ‘platform’ pricing:

So here’s the right way to frame the debate:

If you value SpaceX as a capital-intensive aerospace prime, you’ll call it absurd.

If you value it like a global connectivity platform with proprietary distribution (launch) and vertical integration (satellites + terminals), you’ll call it underappreciated.

If you value it like a platform plus out-of-the-money calls on entirely new markets (direct-to-cell at scale, Starship economics, in-space compute, national security architectures), you’ll accept that the “number” is really a probability-weighted stack of scenarios.

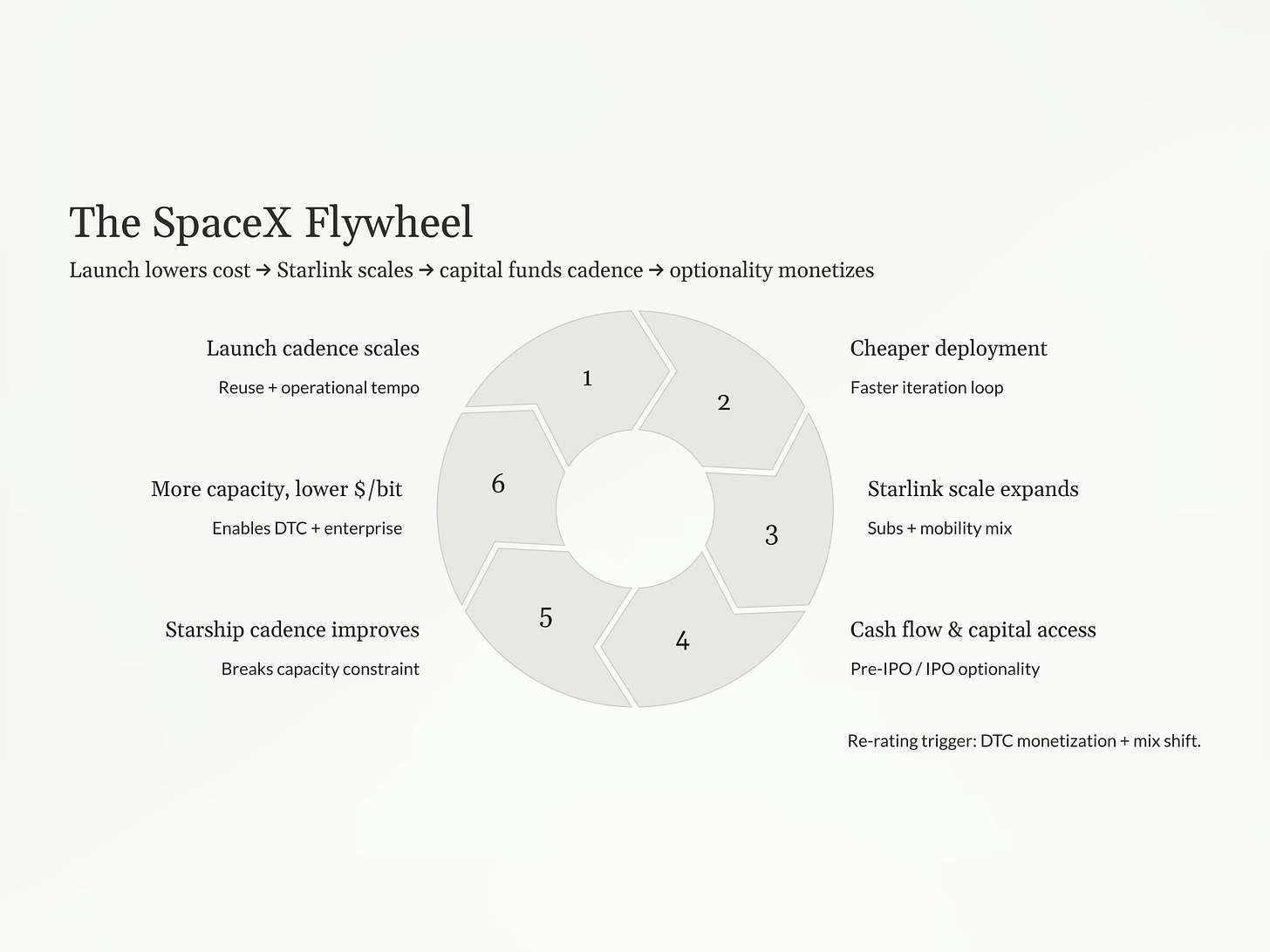

Our bias is cautiously constructive: we’re willing to live with a high headline valuation if the KPI trail keeps validating the flywheel. The key is to stop asking “Is $800B expensive?” and start asking “Which parts are you actually buying?”

The Framing Mistake

Most companies have one dominant engine and a couple of adjacencies. SpaceX has multiple engines, each with different valuation physics:

1. Launch is cyclical, lumpy, and operationally constrained. It deserves “industrial” multiples unless it becomes a true capacity monopoly.

2. Starlink is recurring revenue, consumer-to-enterprise, global by default. It deserves “network/infra” multiples if churn stays low and unit economics scale.

3. Starship + new markets are not a business today—they’re a volatility surface. If you try to DCF them like a mature segment, you’ll either overpay or miss the point.

That’s why public-market investors will split into tribes:

The “Starlink is the whole thing” tribe,

The “launch is the moat” tribe,

The “Starship unlocks everything” tribe,

And the skeptics who say: “It’s just Musk selling a dream with a Wi-Fi router.”

The right approach is sum-of-the-parts with explicit probability weights, plus a clear list of milestones that change those probabilities.

Business A — Launch is the distribution monopoly

SpaceX’s launch business is often described as “mature.” That’s lazy. It’s mature in engineering repeatability, not in market structure.

What SpaceX actually built is the closest thing to a vertically integrated distribution layer to orbit: rockets, pads, turnaround cadence, reusability, and a production system that keeps lowering marginal cost. The tell isn’t rhetorical; it’s tempo. By Dec. 10, 2025, SpaceX had already flown its 160th Falcon 9 mission of the year, and by Dec. 17 it had logged 165 – including boosters pushing 30 flights per core. If nothing else flew before year-end, SpaceX would close 2025 around ~167 Falcon 9 launches.

That cadence is not just a flex – it is the moat. Reuters Breakingviews framed the outcome plainly: SpaceX now puts over 80% of global orbital payload weight into orbit. That’s what “distribution monopoly” looks like in an industry that used to be supply-constrained.

Why this matters for valuation:

Launch is not the cash cow investors daydream about. Even at dominant share, launch is constrained by physics (range availability, weather, national security scheduling), and pricing is still tethered to customer mix.

But launch is the strategic choke point that makes everything else cheaper, faster, and harder to compete with. It is the reason Starlink can iterate satellites like a consumer product, not a traditional aerospace program.

Launch is also how SpaceX subsidizes and accelerates the real engine: Starlink.

So how should you price Launch in SOP terms?

Treat it as a high-ROIC industrial with a structural share advantage, plus embedded call options (new vehicles, new payload classes, national security architecture shifts). The public comps won’t be perfect: primes have different margin structures; satellite operators don’t own distribution; and most “space” peers don’t have comparable cadence.

Launch won’t justify a trillion-dollar market cap by itself – but it can justify the durability of everything else.

Business B — Starlink is the cash engine people keep under-modeling

Starlink is where the valuation debate becomes real because it’s the only segment with platform-like scaling on a hard-asset base competitors can’t replicate quickly.

Public figures vary by date and definition, but the direction is unmistakable. Reuters has described Starlink at 6M+ customers across 140+ countries/territories with ~10,000 satellites in orbit; other reporting around early Nov. 2025 cited SpaceX/Starlink saying it had passed 8M customers. Don’t over-litigate 6M vs 8M – either way, this is one of the fastest-scaled connectivity products on earth.

The IPO tape is already shaping expectations. Reuters reported a secondary share sale priced at $421/share, valuing SpaceX around $800B with up to $2.56B offered, framed as part of 2026 IPO preparation. Reuters also reported IPO planning that could target $25B+ in proceeds, pitched to fund Starship ramp and other capex.

Revenue is the anchor investors are implicitly underwriting: Bloomberg reported SpaceX revenue around ~$15B in 2025 rising to $22B–$24B in 2026, with Starlink as the primary driver; Reuters Breakingviews echoed the same slope and noted how central Starlink is to justify the headline valuation.

This is the core reframing: Starlink is being valued less like “satellite internet” and more like a global edge network – consumer broadband plus high-ARPU verticals (aviation/maritime/enterprise), and eventually direct-to-cell. As a TAM sanity check, ITU estimates ~2.2B people remain offline globally in 2025 – Starlink doesn’t need all of them, just the high-value slice terrestrial networks chronically underserve.

The hidden re-rating lever: direct-to-cell (DTC)

• Expands TAM from terminal buyers to phone users

• Positions Starlink as a wholesale partner to telcos

• Adds bundling distribution that can reduce churn and CAC

Execution is moving from concept to packaging: Reuters noted DTC becoming active in Canada; Rogers launched a Starlink-powered satellite-to-mobile service at C$15/month; and Reuters reported Starlink’s largest DTC deal with Veon (150M+ potential customers) alongside notes that SpaceX operated 8,000+ satellites with ~650 dedicated to DTC. Allied Market Research sizes direct satellite-to-phone at $2.5B (2024) growing to $43.3B by 2034.

Business C — Starship is the option that changes every multiple

Public markets hate uncertainty, but they will pay for uncertainty that can be compressed into a milestone schedule. Starship is that schedule.

Starship isn’t “just a rocket.” It’s a cost curve. If it works on a scale, it changes the unit economics of:

• deploying next-gen Starlink satellites faster and cheaper

• launching large national security payloads

• building in-space infrastructure

• enabling new categories (including space-based AI compute concepts)

In other words, Starship is not valued for what it does today – it’s valued for what it makes cheap tomorrow.

That’s why finance messaging matters. In the IPO-prep context, Reuters reported SpaceX pitching proceeds as fuel for ramping Starship launch activity, alongside ambitious capital stories such as space-based AI data centers and “Moonbase Alpha.” Whether you buy the moonshots or not, the underwriting point is simpler: Starship cadence is the constraint that either validates or breaks the long-term margin narrative.

Reuters Breakingviews made the implied underwriting math explicit: to justify the headline valuation, investors are effectively being asked to believe in something like ~50% annual revenue growth and ~60% EBITDA margin by 2030 (illustrative). Starship is the operational bridge to even have a shot at that margin structure, because it’s the lever that can collapse delivered cost per ton and raise capacity.

So the right question isn’t “Will Starship colonize Mars?” It’s: what’s the probability Starship meaningfully lowers cost and increases capacity within a public-market time horizon?

Marks that change the probability (and the multiple):

• Mark A: repeatable operations with a credible high-cadence rhythm

• Mark B: Starship materially accelerates Starlink’s next-gen constellation rollout

• Mark C: U.S. national security wins scale alongside that cadence

Hit A/B/C within the first public-market window and investors won’t debate whether the valuation is high – they’ll debate how high the multiple can go once the constraint breaks.

The valuation – a clean SOP with explicit marks that change the tape

Let’s price SpaceX the way the market actually argues about it: not as one company, but as three businesses whose “right” multiple changes when specific proof points land.

Step 1: Anchor on the only semi-hard numbers

The latest private-market anchor is not a vibe – it’s a price. Reuters reported SpaceX is running a secondary share sale at $421/share, valuing the company around $800B, with up to $2.56B offered, per a shareholder letter from CFO Bret Johnsen.

In parallel, Reuters reported a 2026 IPO is being explored, potentially raising $25B+ and implying a valuation above $1T, with banks already in a “bake-off.”

Now marry that to the revenue slope the market is underwriting. Bloomberg reported SpaceX revenue around ~$15B in 2025, rising to $22B–$24B in 2026, with Starlink as the primary driver.

At $800B, you’re paying roughly ~33x–36x 2026 revenue (illustrative math). That’s not “aerospace.” That’s “platform pricing.” The entire valuation debate is therefore a Starlink debate.

Step 2: Think in parts, not one multiple

A clean SOTP isn’t about being precise. It’s about being falsifiable.

Part 1: Starlink (Connectivity + Direct-to-Cell optionality)

Base case: valued like global infra/network with recurring revenue + growth

Bull case: valued like a scaled platform with carrier bundling and enterprise mix shift

Bear case: churn rises, capacity constraints bite, regulation/spectrum frictions grow

Part 2: Launch (distribution monopoly that protects everything else)

Launch is not the trillion-dollar story – it’s the choke point that makes Starlink iteration cheap and fast. It deserves a moat premium, but its multiple ceiling is lower than Starlink’s.

Part 3: Starship/Other (options that become segment value if cadence de-risks)

Reuters reported IPO proceeds are being pitched to fund Starship ramp and even ambitious projects like space-based AI data centers and “Moonbase Alpha.”

That’s not near-term margin – that’s option spending. The market will pay for it only when Starship compresses uncertainty into a credible cadence.

Step 3 – Benchmarks: the “world” the tape is choosing

The market is already telling you which benchmark set it wants:

· If SpaceX is priced off 2026 revenue, you are in a platform/infra benchmark world, not an aerospace one.

· Reuters Breakingviews has framed the implied underwriting more bluntly: to support “$1T+” talk, investors are being asked to believe in something like ~50% annual revenue growth and ~60% EBITDA margin by 2030 (illustrative).

So the honest valuation question is not “is $800B expensive on 2026 sales?”

It’s “what probability do you assign that Starlink + Starship can make the 2030 shape believable?”

Step 4 – The marks that change the multiple

Three marks can legitimately re-rate the tape around the IPO window:

Mark A (Starlink economics): net adds stay strong while churn stays stable, with mix shifting into higher-ARPU verticals.

Mark B (DTC monetization): repeatable carrier deals with visible wholesale/rev-share economics (beyond pilots).

Mark C (Starship credibility): cadence rises and delivered cost per ton becomes increasingly legible.

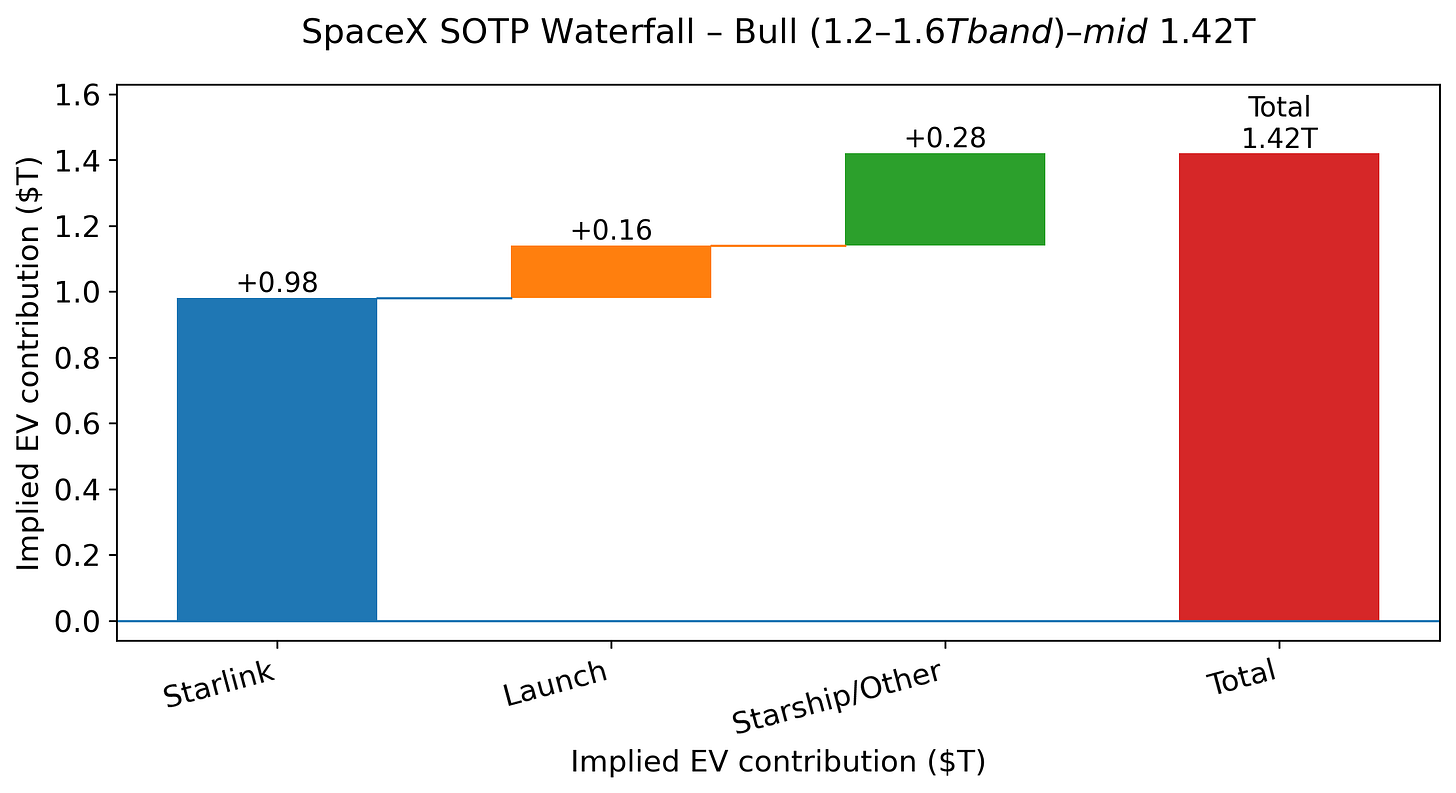

Step 5 – What the tape can trade: an illustrative SOTP range

This is an illustrative range to make disagreement measurable — not a forecast.

Implied today (~$800B): Starlink carries most of the EV; Launch is the moat; Starship/Other is the option.

EV bands (illustrative):

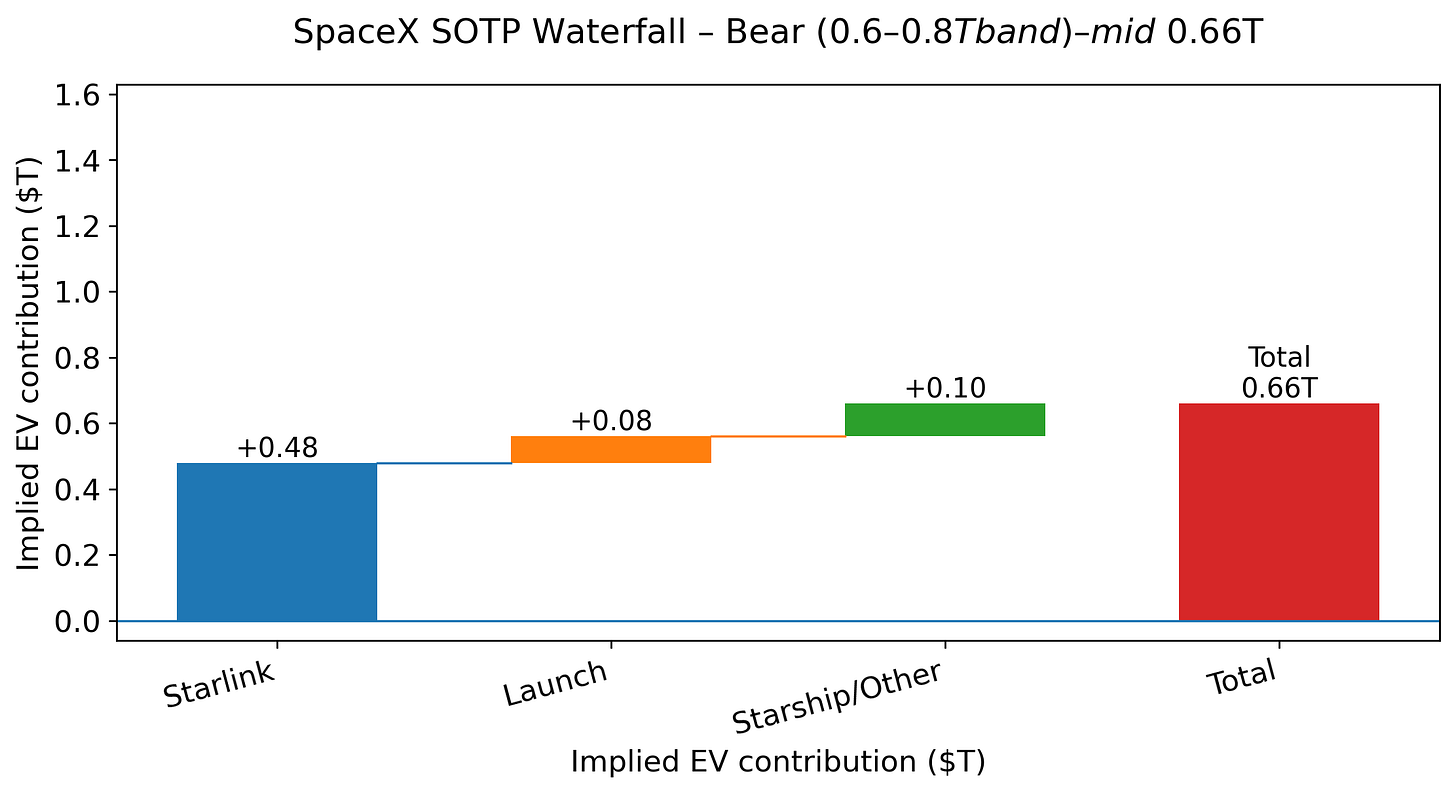

Bear (industrial + telco de-rate): $0.6T–$0.8T

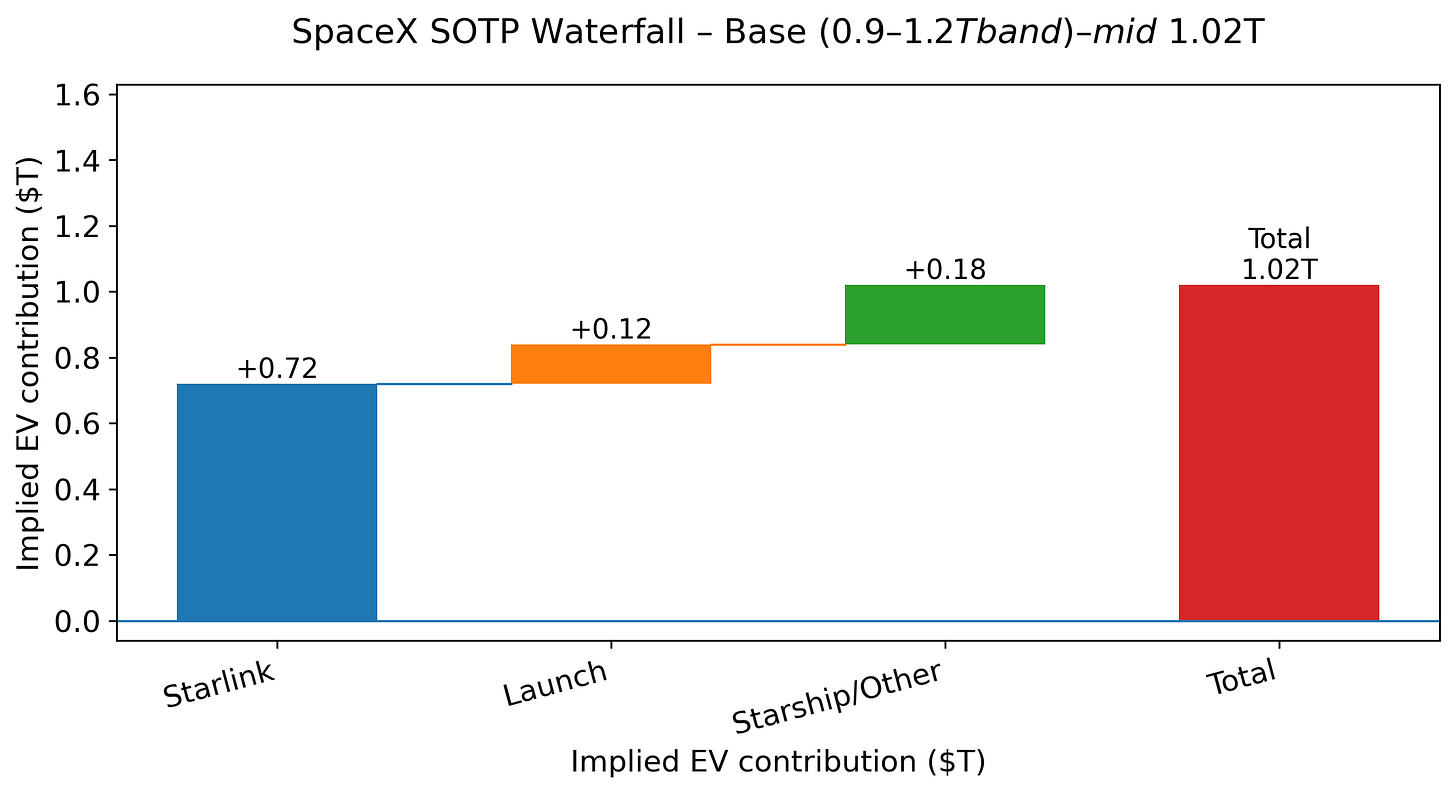

Starlink $0.4T–$0.55T | Launch $0.06T–$0.10T | Starship/Other $0.05T–$0.15TBase (global infra + network premium): $0.9T–$1.2T

Starlink $0.6T–$0.85T | Launch $0.09T–$0.14T | Starship/Other $0.10T–$0.25TBull (A+B+C land quickly): $1.2T–$1.6T

Starlink $0.85T–$1.10T | Launch $0.13T–$0.20T | Starship/Other $0.20T–$0.35T

Bear scenario (what breaks the multiple): governance/key-person risk, geopolitical haircut, and capex fatigue that forces a “industrial + telco” reframe.

What I’m watching: the 8 KPIs that matter more than the headline valuation

Starlink net adds and churn (direction matters more than absolute)

Enterprise/aviation/maritime mix shift (margin and ARPU quality)

Direct-to-cell: carrier count, geography, attach economics

Satellite capacity growth vs demand growth (is congestion creeping in?)

Launch cadence stability + mishap frequency

National security wins (Starshield and related architecture)

Starship cadence milestones (probability update engine)

Capital allocation transparency as IPO nears (what gets funded, what gets delayed)