The “Gray Rhino” Behind the U.S. AI Rally

AI is lifting productivity and mega-cap valuations even as the U.S. middle class’s income base quietly erodes.

Highlights

AI’s boom is masking a growing gray-rhino risk: large-scale, AI-enabled white-collar layoffs that threaten the middle-class income base supporting U.S. consumption.

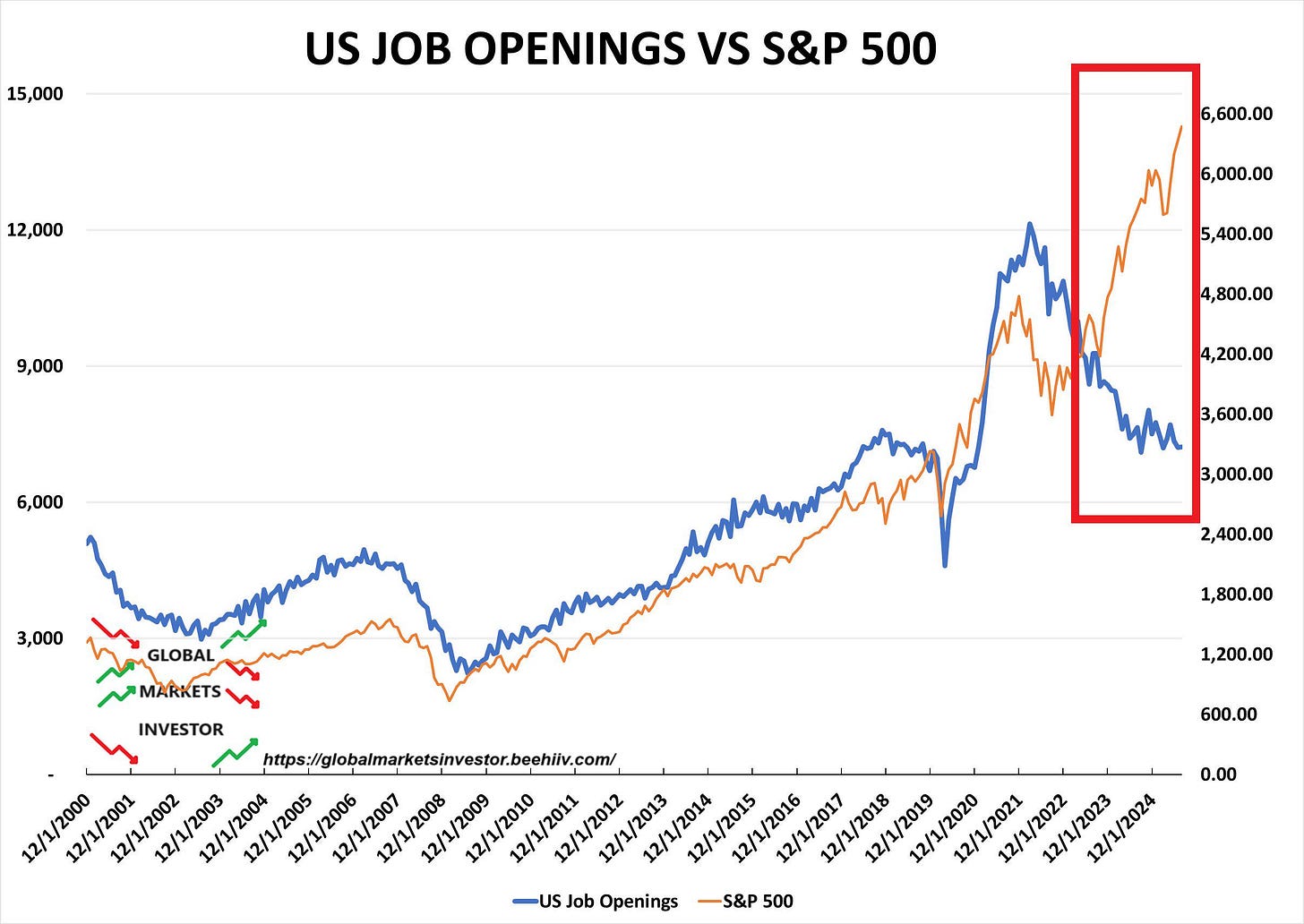

The current “Goldilocks” loop is fragile: easy money, AI capex and concentrated wealth effects are pushing equities and productivity higher, even as job openings and consumer expectations quietly deteriorate.

Rate cuts may deepen the problem: cheaper capital accelerates AI investment and labor substitution, raising the odds that the next downturn is driven not by inflation or credit, but by a sharp collapse in middle-class spending — a risk investors should monitor in consumer-exposed and mid-market service names.

U.S. AI stocks are soaring. Productivity data are ticking higher, mega-cap capex is breaking records, and Nasdaq futures keep setting new highs. On the surface, the AI boom looks like a textbook case of technology-driven optimism.

Underneath, the more important risk in this cycle may not lie in credit markets at all. It sits in the labor market — specifically, in the income stability of the U.S. middle class that underpins consumption. As companies roll out AI tools at scale, they are starting to do something they carefully avoided in the earliest phase of the boom: cutting white-collar jobs in large numbers.

In late October, two U.S. giants announced layoffs almost simultaneously: UPS and Amazon, together planning job cuts close to 100,000. Other firms that did not make the front pages — Microsoft, for example — prefer the “death by a thousand cuts” approach: no splashy announcements, just a steady stream of “optimization.”

This time, the workers being replaced are some of the highest-quality white-collar jobs in the U.S. economy. As AI tools spread, corporate managers have finally found their ultimate “cost-cutting and efficiency” machine: replacing opex with capex — capital expenditure on AI infrastructure instead of operating expenditure on human staff.

For many middle-class households, that translates into falling income and a much more uncertain future. If this wave of layoffs continues to broaden, it could become one of the most underestimated gray rhinos for U.S. equities in 2026.

AI Layoffs: From Headlines to Economic Reality

It is tempting to dismiss the recent layoff headlines as isolated moves — a few logistics and tech firms “right-sizing” after over-hiring during the pandemic. But several features of this round of cuts look different.

First, the timing: these layoffs are coming not in the depths of a downturn, but in the middle of what still looks like a strong AI-driven expansion. Second, the type of roles at risk: customer support, sales, operations, middle management, and even some analytical and coding jobs — precisely the kind of white-collar positions that were once seen as relatively insulated.

Third, the toolkit: unlike previous cycles, companies now have a credible technological substitute. Generative AI and automation systems can handle a growing share of repetitive knowledge work. That gives CFOs a clear trade-off: higher upfront capex for data centers, models and software licenses, in exchange for structurally lower wage bills over time.

Individually, each announcement is manageable. Collectively, if the pattern persists, it changes the character of the cycle. The marginal dollar of corporate spending shifts from labor to capital. The stock market can celebrate higher margins. The real economy has to deal with weaker income growth across a broad slice of the middle class.

(Exhibit: The divergence between employment metrics and the S&P 500 opened up right as the AI trade took off.)

Source: Reddit (r/EconomyCharts)

The Fragile “Goldilocks” Loop: AI’s Promise Rests on a Delicate Balance

Over the past two years, the U.S. economy has been living in what looks like a Goldilocks loop — not too hot, not too cold.

On the corporate side, mega-cap tech firms have been deploying the enormous cash piles they accumulated in the previous decade. Their investment in AI infrastructure — chips, data centers, networking, power and cooling — has provided a powerful demand impulse across the supply chain. Orders flow to semiconductor designers, foundries, equipment makers, utilities and specialized real-estate operators.

On the financial side, global capital has been chasing the AI theme. Aggressive thematic vehicles and crossover funds have brought in relatively cheap money from Japan and Europe, amplifying the upside scenarios around the entire AI value chain. Valuations stretch, but as long as earnings and capex keep surprising to the upside, the market can live with it.

On the household side, excess savings accumulated during the pandemic, together with rising asset prices, have cushioned the impact of higher rates. Corporate profits have been recycled into investment and buybacks without yet triggering obvious debt-sustainability alarms.

The macro data, taken at face value, have looked acceptable. Productivity appears to be improving at the margin. Headline unemployment remains low. Inflation has moderated from its peak. In that environment, even a gradual cooling of the labor market can be offset — at least in part — by the Federal Reserve’s willingness to cut rates.

But this balance is more fragile than it looks. It relies on a crucial assumption: that the core of the middle class remains employed and willing to spend.

Middle-Class Job Losses: The Most Dangerous Layer

In recent months, the U.S. labor market has settled into a curious “weak equilibrium.” At the lower end, labor supply has shrunk: stricter immigration enforcement and deportations have contributed to stress in areas like trucking, while many low-end service jobs remain hard to fill. That has put a floor under wages in some segments.

At the same time, middle- and higher-income households have continued to support consumption. They have mortgages and childcare to pay, portfolios to protect and lifestyles to maintain. As long as they stay employed, the overall consumption numbers can look better than the underlying distribution would suggest.

The key precondition for this structure is simple: the middle class must not lose its jobs.

AI is now testing that precondition. Once companies like Microsoft and Amazon — employers heavily tilted toward white-collar staff — start cutting headcount, and once AI capex and layoffs move more or less in lockstep, the labor market risks tipping into a regime of significant oversupply at the top end: rising white-collar unemployment and very limited openings for high-income roles.

If this fragile equilibrium in the upper tiers of the labor market breaks, the pressure will show up in U.S. consumption both today and in expectations for tomorrow. Surveys are already hinting at this. The Conference Board’s Expectations Index has weakened, with respondents more pessimistic about future business conditions and job availability, and less optimistic about future income.

The problem is compounded by the uneven transmission of the AI bull market’s wealth effect. The main beneficiaries so far have been the big tech platforms and high-net-worth investors. For middle-class families with modest assets and increasingly shaky jobs, there has been no obvious AI dividend and no visible income boost.

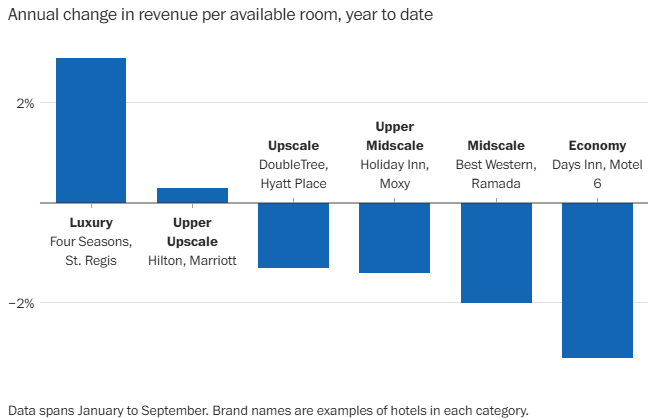

One way to see this divergence is through the hotel sector. In the U.S., only the top-tier luxury properties are still pushing through price hikes. Mid-range and budget hotels have already rolled over. That suggests the “wealth spillover” from the AI rally is extremely concentrated, and that conditions on the broader consumer front remain tepid.

On equity forums, investors are openly saying things like: “I’m not buying AI stocks to make money; I’m buying them to hedge against being replaced by AI.” This generation of investors is treating equity holdings as a form of unemployment insurance.

(Exhibit: Only the most luxurious hotel categories are still raising rates — a telling side indicator.)

Source: CoStar, via The Washington Post.

A Perverse Loop: The More the Fed Cuts, the Worse Jobs May Get

The Federal Reserve will most likely continue to cut rates in an effort to stabilize employment and support valuations. Recent communication has emphasized risk management and the desire to avoid an unnecessary hard landing. Market pricing suggests a strong probability of further easing in the coming quarters.

The problem is that the more the Fed cuts, the hotter AI capex runs — and the stronger the incentive for firms to shed labor. Lower discount rates make long-duration projects more attractive, and AI infrastructure is the quintessential long-duration bet: high upfront cost, uncertain but potentially large payoff, and substantial operating leverage.

This creates a seemingly benign, but in fact dangerous, feedback loop:

Weaker employment → markets price more cuts → cheaper capital fuels AI → AI accelerates labor substitution → employment weakens further.

On paper, the Fed is supporting employment. In practice, its lower cost of capital may be helping large firms “optimize” more jobs away. The loop can keep running smoothly — like a perfectly lubricated machine — until one key component suddenly fails.

The most likely point of failure is consumption. Once middle-class households begin to fear prolonged job insecurity, they can respond quickly: cutting discretionary spending, delaying big-ticket purchases, trading down in travel and leisure, and rebuilding cash buffers. Given the weight of services and consumption in the U.S. economy, it does not take a large change in behavior to show up in the data.

What This Might Mean for Investors

For now, the clear structural winners of the AI boom remain the leaders and infrastructure suppliers with strong balance sheets and pricing power. The more vulnerable parts of the market sit in the middle: consumer and service businesses heavily reliant on U.S. middle-class discretionary spending, and companies that are slow to adopt AI but still face rising wage and financing costs. Over the next 12–18 months, the key gauges to watch are white-collar job openings, consumer-expectations surveys, and the breadth of earnings growth beyond the AI complex. A persistent deterioration there would argue for a more cautious stance toward the “middle” of the market, while staying selective at the ends of the barbell where AI is either a clear structural tailwind or a clear structural threat.

Conclusion: The Gray Rhino Is Not the End, but the Start of a New Reset

The story of the AI boom will not end with a wave of layoffs. As in every past industrial revolution — cars replacing coachmen, email displacing mail carriers — incremental innovation and destructive change move together. Every technological leap for humanity comes with a bill that someone has to pay.

What makes this cycle distinctive is how quickly the labor-market side effects are colliding with the macro narrative. The AI rally is not just a tech story; it is a story about income stability, social risk-sharing and who ultimately bears the cost of higher productivity.

For now, markets are still focused on the upside: earnings beats, capex guidance, model launches and data-center footprints. As long as those remain strong, AI-exposed equities can continue to perform, and the wealth at the top can continue to grow.

The gray rhino in this cycle is not an obvious credit event or a sudden policy shock. It is the slow, heavy pressure of middle-class stress — white-collar job losses, weakening expectations and a gradual pullback in spending — building up behind the scenes.

The U.S. equity market is no longer being asked only whether AI is “worth its valuation.” It is being pushed to answer a harder question:

As AI grows ever more powerful, what happens to ordinary people — beyond using the Nasdaq as a hedge against their own obsolescence?

Excellent analysis! Your consistent focus on technology's economic ripples, like this gray rhino, is so insightful, especialy for us in AI.