When Everything Becomes a Bet: Polymarket, Labubu, and the Gamblification of Risk

In a low-growth, high-anxiety world, we’ve built cuter casinos and smarter odds - but not better outcomes.

1. Everything Is Now a Ticket

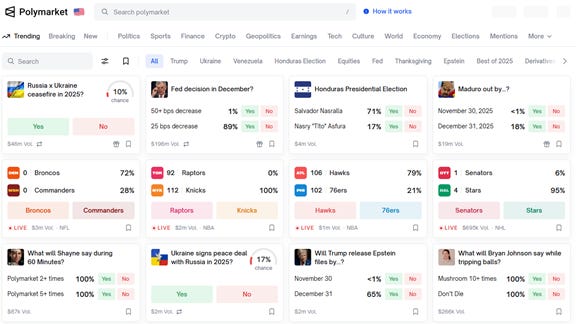

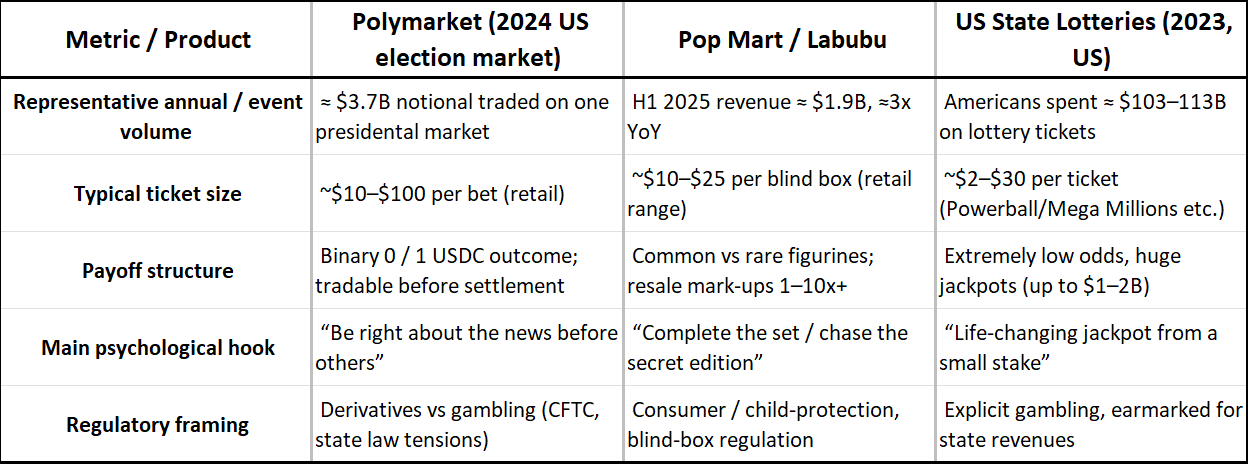

Open Polymarket on any given day and the world looks like a giant options chain. One single contract - “Who will win the 2024 U.S. presidential election?” - ultimately saw about $3.7 billion in volume change hands before it settled in November 2024. A French “whale” reportedly staked tens of millions of dollars on Donald Trump, walking away with around $85 million in profit once the race was called. What used to be the domain of polling nerds and political junkies has become, quite literally, a multi-billion-dollar bet.

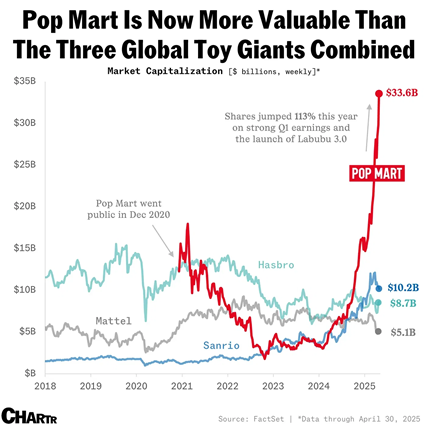

On the other side of the world, a small sharp-toothed elf called Labubu has turned a Hong Kong-listed toy company into something that looks suspiciously like a luxury stock. Pop Mart’s shares have climbed roughly 470% over the past year, lifting its market value to about HK$367 billion (≈$47 billion) - more than Mattel, Hasbro and Sanrio combined. In the first half of 2025 alone, Pop Mart’s revenue surged to roughly 13.9 billion yuan (≈$1.9 billion), more than tripling year-on-year, while net profit jumped nearly fourfold. The company now runs hundreds of branded stores and thousands of vending “roboshops” in multiple countries, and rare Labubu pieces have changed hands at auction for very high five- and six-figure prices.

One platform lets you bet on elections and interest rates; the other sells opaque boxes of collectible toys. They look completely different. Yet both are built on the same idea: in a low-growth, uncertain world, turn uncertainty itself into a product - and let people pay for the chance to be right.

This essay is about that common logic. We’ll start by looking at how Polymarket and Labubu actually work, then zoom out: why do these “lottery-shaped” pay-offs thrive in an era of stagnation and anxiety, what are the economic and social costs, and is there anything genuinely useful buried inside the casino?

2. Two Products, One Logic

2.1 Polymarket: Turning News into Binary Contracts

Polymarket describes itself as a prediction market, not a casino. Technically, that’s true. Each contract represents a real-world question - “Will the Fed cut rates by 25bp in September?”, “Will Trump win the presidency?”, “Will Bitcoin trade above $100,000 by year-end?” - and trades between 0 and 1 USDC. The price is literally the market-implied probability; at settlement, correct outcomes pay out at 1, losers go to zero. There is no house setting fixed odds. Orders are matched peer-to-peer, and traders can exit before resolution, locking in profits or losses as probabilities move. At any given time, the platform lists a large number of live markets, ranging from hard macro data to sports and pop culture.

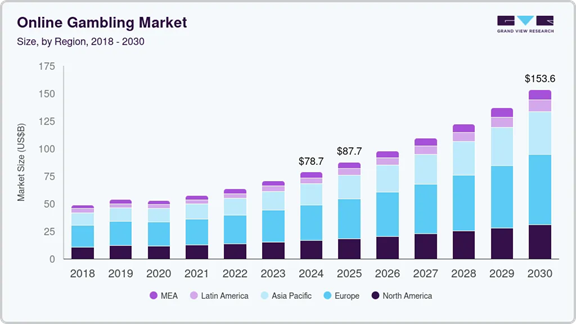

This is no longer a niche crypto toy. By 2025, Polymarket counted an estimated few hundred thousand active accounts, while regulated rival Kalshi reported about 2 million U.S.-verified users. Intercontinental Exchange, the owner of the New York Stock Exchange, has agreed to invest up to $2 billion in Polymarket at a multi-billion-dollar valuation, and will distribute the platform’s event-probability data to institutional clients. That is a level of capital and infrastructure usually reserved for listed exchanges, not side-hustle betting apps - yet the underlying contracts are still binary bets on real-world events.

The legal system hasn’t fully decided what to do with this. Polymarket has negotiated a path back into the U.S. under the CFTC’s derivatives framework; Kalshi has fought to list contracts on everything from Federal Reserve policy to which party controls Congress. At the same time, a Nevada federal judge recently ruled that parts of Kalshi’s offering fall under state gambling law, not federal derivatives jurisdiction - a reminder that regulators themselves can’t quite agree whether these are “innovative financial instruments” or simply online sportsbooks with better branding.

2.2 Labubu: A Lottery Wrapped in Vinyl

Labubu, by contrast, looks like the opposite of finance - a cute fang-toothed elf sitting on millennials’ bookshelves. Yet the numbers put it firmly among serious assets. Pop Mart’s revenue has grown at a compound annual rate of more than 70% since 2020, and the company is now worth more than Hasbro, Mattel and Sanrio combined. In 2024, the series that Labubu belongs to (“The Monsters”) generated almost 35% of Pop Mart’s revenue, raising questions about how dependent the company has become on a single viral IP. Pop Mart now runs hundreds of physical stores and thousands of vending machines across multiple continents, selling into a collectibles market estimated at more than $40 billion a year. Its gross margin, around the high-60s, looks more like a luxury goods group than a traditional toy maker.

The engine behind this is not utility, but engineered uncertainty. Labubu is sold primarily through blind boxes: you pay a fixed price for an opaque box containing a random figurine, with a tiny chance of drawing a rare edition worth many times the ticket price - sometimes hundreds or thousands of dollars on resale platforms. Economically, consumers are buying expected utility - the average value of common and rare items - plus the emotional payoff of anticipation. Behaviorally, the design leans on loss aversion, sunk-cost effects (“I’ve already bought five, I might as well chase the rare one”) and social proof amplified by unboxing videos and influencer collections. In other words: this is a lottery dressed up as lifestyle retail.

Polymarket and Labubu sit at very different points on the cultural map. One speaks the language of “probabilities”, “markets” and “information”; the other speaks in memes, cuteness and fandom. But if you zoom in on the payoff structure and the behavior it encourages, they start to look uncannily similar.

3. From Investing to Gambling: The Gamblification of Risk

Strip away the branding and both products share the core traits of gambling.

Structurally, Polymarket contracts are binary options with short horizons and lottery-like pay-offs: most contracts either go to zero or to par, and traders are rewarded for taking leveraged views on narrow slices of reality. Labubu’s blind boxes embed a similar payoff: a small chance of drawing a rare figurine worth many times the ticket price, subsidized by a large pool of common buyers. In a collectibles’ market now worth tens of billions of dollars globally, these lottery-style pay-offs are not a sideshow; they sit at the heart of how “emotional assets” are being sold.

Behaviorally, the mechanisms are designed for dopamine, not balance sheets. On Polymarket, you can change your mind and trade in and out as polls shift, headlines flash and whales place giant orders - turning politics and macro into an always-on game of “guess the next tick”. In Labubu’s world, the randomized reveal, the chase for complete sets and the visible resale prices on secondary markets all encourage repeat purchases and sunk-cost reasoning.

This is exactly what academics now call the “gamblification of investing”: products that tend to make most users lose money, attract individuals already at risk of gambling harm, and borrow the design tricks of casinos - high frequency, constant feedback and the lure of big lottery-like wins. Whether the UI is a DeFi dashboard or a pastel-colored toy shelf is, in that sense, a cosmetic choice.

To understand why this model is thriving now, we have to look beyond product design and into the macro backdrop.

4. Low-Growth, High-Anxiety Economics

The timing of both booms is not accidental. Pop Mart’s explosive growth did not happen in the middle of a roaring, broad-based consumption boom. It happened in an economy where many traditional categories - from premium spirits to mass retail - were slowing, while “emotional consumption” brands were posting triple-digit growth. Pop Mart’s first-half of 2025 sales jumped to around $1.9 billion, roughly triple the level of a year earlier, and already exceeded its full-year 2024 revenue. In Japan’s “low-desire society”, young people responded to stagnant wages and shrinking prospects by retreating into anime, games and collectibles. China’s recent data suggest a similar pattern: when upward mobility feels out of reach, a 100-yuan figurine that delivers a jolt of joy and a sense of belonging can look more rational than a 30-year mortgage.

Gambling data shows a related pattern. Studies of U.S. state lotteries find that ticket sales tend to rise as unemployment rises - one widely cited estimate suggests roughly a 0.17% increase in lottery sales for every 1-percentage-point increase in the state unemployment rate - even though aggregate national lottery revenue dipped somewhat during the 2008 recession and casino spending stalled. In other words, the relationship between economic stress and gambling is nuanced, but a consistent thread runs through it: when people feel stuck, they gravitate towards small, high-volatility bets that offer psychological escape and a thin shot at outsized change.

Polymarket rides a different facet of the same mood. Post-Covid, macro uncertainty has become a permanent feature rather than a tail event. Central banks pivot repeatedly, wars drag on, AI narratives whiplash. Against that backdrop, a platform that turns “Who will win?” and “Will they cut?” into tradable odds offers something people crave: the illusion of agency over chaos. For some, a $50 bet on the Fed’s next move is not that different from a Labubu blind box - both are small, high-variance wagers in a world they no longer feel they can influence through traditional careers or long-term investing.

The result is a kind of micro-hedging against macro anxiety. When the big levers of life - housing, career, pension - feel broken or out of reach, people reach for products that let them at least gamble on the dice, even if they don’t control the table.

5. The Downside: Balance Sheets, Market Structure, Institutions

It’s tempting to treat all of this as a harmless sideshow - people have always bought lottery tickets and collectible toys. But the scale, design and institutional embedding of today’s betting-shaped products make the downsides harder to ignore.

At the individual level, the risks are straightforward. Products that combine binary payoffs, frequent feedback and strong social signaling are catnip for anyone with a gambling-prone psychology. Blind boxes and meme coins offer a steady stream of near-misses and small wins that encourage “just one more try”; prediction markets offer constant opportunities to “trade the news” with leverage-like exposure. In both cases, the long run expected return for the median user is likely negative, especially once transaction costs and platform economics are considered. These are not balance-sheet-friendly products for fragile households.

At the market-structure level, the picture is no cleaner. Polymarket’s disputes over how to define “a suit” or whether a vague memorandum counts as a “rare earths agreement” show how hard it is to settle supposedly binary contracts in messy real-world situations. When resolution is delegated to token-voting oracles, the risk of “tyranny of the majority” and whale influence is real. The Trump “whale” who poured tens of millions into pro-Trump contracts during the 2024 election not only made a life-changing profit; his trades also shifted market odds that flowed into terminals, news articles and social feeds, feeding a narrative of Trump momentum. At some point, prediction markets stop reflecting reality and start helping to create it.

Meanwhile, a rapidly growing layer of event contracts now covers everything from war casualties to the election of a new pope, with individual markets attracting tens of millions of dollars in volume and paying out five-figure sums to successful speculators. On the consumer side, blind-box ecosystems can become dominated by professional resellers and arbitrageurs, leaving ordinary fans buying at the top of a carefully engineered scarcity cycle.

Regulators are beginning to notice. The Nevada ruling against parts of Kalshi’s offering was loudly cheered by traditional sportsbooks that see prediction markets as a competitive threat. In Beijing, commentary about tightening rules on surprise-box sales and collectible cards - motivated by concerns about child addiction - has already knocked Pop Mart’s share price. In Washington, the same agencies that regulate derivatives are now wrestling with questions that look more like moral philosophy: Should you be allowed to bet on how many people die in a war? On whether a politician is assassinated? On how will a jury rule in a high-profile criminal case? When tragedy itself becomes a tradable underlier, the question is no longer “Is this efficient?” but “What kind of society do we want to be?”

6. The Upside: Information and Insurance, If We’re Careful

None of this means prediction markets are useless or purely harmful. In fact, the academic record for well-designed, low-stake markets like the Iowa Electronic Markets is surprisingly strong. One study comparing IEM prices with 964 opinion polls across five U.S. presidential elections from 1988 to 2004 found that the market was closer to the final vote share roughly 74% of the time. The underlying logic is straight out of Hayek: dispersed, local knowledge about “particular circumstances of time and place” can be aggregated through prices better than through surveys or expert panels, especially when participants have real money at stake.

Polymarket pushes this into the age of information finance. Its odds now appear on terminals; large financial institutions such as Intercontinental Exchange are investing at multi-billion-dollar valuations to plug its data into mainstream market infrastructure. Rival platforms talk openly about building “event derivatives”, allowing corporates and investors to hedge risks that don’t fit neatly into existing instruments: specific regulatory decisions, climate outcomes, even the results of major antitrust trials.

In that world, prediction markets become less like an online casino and more like a high-frequency, crowd-sourced probability surface for the future - a complement, not a replacement, for fundamentals. Used carefully, they can sharpen scenario analysis, discipline narrative-driven research and provide early warning when the crowd’s risk perception moves faster than traditional economists or strategists.

On the consumer side, Labubu-style products arguably perform a softer kind of financial function. They slice “aspirational consumption” into 100-yuan tickets, letting young buyers access a sense of art, identity and even status - owning the same figurine as a celebrity - without committing to a mortgage or a four-figure luxury bag. In that narrow sense, they are a way to hedge existential anxiety with small, tangible bursts of joy. The question is what happens when the lottery logic overwhelms the lifestyle one.

The line between useful insurance and addictive gambling, in other words, is not drawn by technology. It is drawn by design choices and regulation.

7. How Investors Should Use (and Not Use) These Markets

For investors, the right response is not to dismiss these markets as noise, nor to dive in head-first as punters. It is to treat them as sentiment instruments and regime indicators, not core assets.

When prediction volumes on political and macro contracts spike into the billions - as they did with the recent U.S. presidential market - and when meme coins and blind boxes are ripping higher on social-media hype, that usually tells you something about risk appetite, liquidity conditions and the market’s tolerance for tail risk. It can inform how much beta, duration or leverage you want elsewhere in the portfolio. You don’t need to trade the election market directly to learn from the pricing of that risk.

Second, investors need a mental checklist for spotting gamblified products. Binary or lottery-like pay-offs; high-frequency feedback loops; heavily gamified interfaces; a user base skewed toward inexperienced, lower-income players; business models that rely on breakage and churn rather than long-term value creation. Both Polymarket and Labubu tick enough of these boxes that they should sit firmly in the “speculation / entertainment” bucket, not the “long-term investment” one.

Finally, if you are building products on top of news and AI - like we are - you can borrow the information layer of these markets without importing their casino layer. Use event odds as an input into scenario analysis; use Labubu-style craze data and toy-collectibles growth as a proxy for retail risk appetite; but design your own tools to slow people down, surface trade-offs and pull them back from slot-machine behaviors. The future of finance doesn’t have to be more addictive to be more useful.

In a low-growth, high-anxiety world, the temptation is to treat everything as a ticket - every news item as a binary bet, every cute object as a scratch card. Polymarket and Labubu show how powerful, and how profitable, that temptation can be. The job of serious investors is not to pretend the casinos don’t exist. It is to understand exactly how they work, what they are telling us about human risk preferences - and to make sure we are not the ones being used as chips.

Sources & Credits

This piece is drawn on:

Company disclosures from Pop Mart and public information from major prediction-market platforms.

Financial and business media reporting from outlets including Bloomberg, Financial Times, Reuters, Barron’s and other reputable news organizations covering Pop Mart, Labubu, Polymarket, Kalshi, U.S. sports betting and the global online gambling industry.

Academic research on prediction markets and gambling, including work on the Iowa Electronic Markets’ election-forecast performance and recent reviews of the “gamblification of investing” and the relationship between unemployment, lottery sales and problem gambling.

Any errors or interpretations are, of course, our own.

Thanks for reading, comments welcome.